In coastal cruising, good seamanship means knowing when to follow the channel—and when it’s smart to stray. As we covered in our on Rule 9 post, blind faith in routes (even trusted ones like Bob423’s) can backfire. To cruise safely and efficiently, you need to understand the purpose of marked channels, how they relate to your vessel and surroundings, and how to interpret Aids to Navigation (AToN) such as buoys, daymarks, lights, and more, is key to safe, efficient cruising.

Let’s break it down.

Marked Channels: What Are They For?

- These are deep, wide, straight, and clearly labeled with scaled-up, numbered aids to navigation spaced for large, fast-moving vessels.

- They’re often part of a larger traffic separation scheme (TSS) near major ports.

- They might be the only dredged route through an inlet or harbor.

When to Stay in the Channel

- Inlets, rivers, and shoal-prone areas: These are no-brainers. Charted depths outside the channel can be unreliable or outdated—especially in dynamic coastal areas where sandbars shift with the tides. Even the buoys themselves may naturally shift frequently, meaning your charts could be out of date before you even download them. Check the Local Notices to Mariners (LNMs) before heading out, and in these areas, trust the marks on the water more than the data on the chart.

- Inland waterways like the ICW and Western Rivers: These systems are often dredged just wide enough for safe passage. Just a boat length outside the marks, depths can drop off fast. On Georgia’s ICW or some “less deep” parts of the Western River system (Mississippi, Tenn-Tom, Arkansas, Ohio, Atchafalaya, etc.), staying in the channel isn’t just smart—it can be survival.

- Harbors, marinas, fairways, and approaches with wrecks, rocks, fishing equipment, or known obstructions: Straying off-course to shave a few minutes might cost you a prop—or worse. If charts and markers agree, heed them.

- Unfamiliar waters or limited visibility: When in doubt, follow the AToNs. Unless you’re dead sure what’s outside the channel, don’t gamble. This is when markers earn their keep.

When It’s OK to Leave the Channel

- Open, deep, unobstructed waters: In many places, especially on the ICW or along the coast, the marked channel may be deeper than you need. If your vessel drafts 3 feet and the adjacent water is consistently 7+, you may have some freedom—as long as you’re confident in your local knowledge, the data, and that your situational awareness is sharp.

- Avoiding commercial traffic: If a large ship (or tug and barge) is bearing down on you in a tight channel, and you’ve got safe water outside, it’s not just smart—it’s indisputable best practice to give way and move out (even to stop and wait). Just don’t cross directly in front of a ship unless you’re doing so at a proper angle and with plenty of room to spare—and, even then, it might be unwise. When in doubt of a maneuver around large vessels, call them on VHF 13 (usually, try 16 if you don’t get through) BEFORE changing course. If they advise against it, it is certainly for good reason. Remember, these commercial mariners likely know the waterway better than you. Defer to their advice.

- Anchoring: You’ll obviously need to step out of the marked route to find good holding ground and swing room. Just make sure your chosen spot doesn’t put you or your anchor line in the path of others.

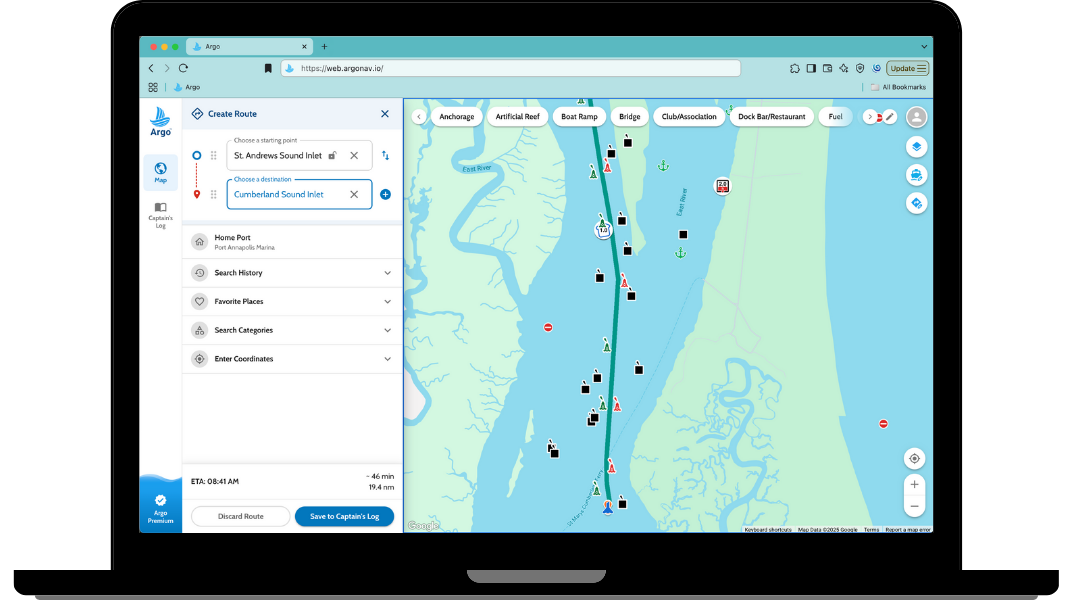

Autorouting and Bathymetric Logic

Some navigation tools, like Argo, offer autorouting that relies not on buoyage systems, but on bathymetric data—essentially calculating routes based on your boat’s draft and available water depth, with (in Argo’s case) a user-defined buffer. This can be especially helpful in less-trafficked or poorly marked areas, where depth—not buoy position—is the most relevant factor.

However, this kind of autorouting has its limitations:

- It may lead you outside of marked channels, which can be perfectly safe—or not. Marked channels exist for a reason, often reflecting years of local knowledge, dredging patterns, and hazard avoidance.

- Bathymetric data can be outdated or incomplete, especially in shifting environments like inlets, shoal zones, and hurricane-prone coastlines.

- The buffer you set in Argo matters. We recommend a safety margin of at least 2× your draft to account for the “squat effect”—especially when autorouting outside known channels. Slower, deeper-draft displacement boats tend to squat less, so they might get away with a smaller buffer. But doing so increases the risk of grounding.

Autorouting is a valuable tool, but it’s just that—a tool. Use it alongside your charts, your eyes, and your judgment.

Argo is actively working on an enhanced routing engine that will offer multiple route options—including one that prioritizes staying within marked channels when appropriate. This future update aims to give users even more flexibility based on their vessel type, conditions, and preferences.

Traffic Separation Schemes & Crossing Channels

If you’re navigating in a traffic separation scheme (TSS) and deep-water shipping channels, like those near major ports, Rule 10 applies (most TSS zones in U.S. waters fall under the International Rules—COLREGS—not the Inland Rules. Check the charted demarcation lines to know which rules apply):

- Recreational boats are allowed but must not impede commercial traffic.

- Cross only at right angles, quickly and cleanly.

- Don’t linger or drift near entrance channels or TSS lanes.

- Stay clear of restricted maneuverability vessels, like tankers or container ships—they can’t easily avoid you.

Buoyage Basics – IALA System B (That’s Us)

Note: System A, used in most of the world outside the Americas, flips some of these conventions. If you’re heading abroad, take time to review that system before you cast off.

In North America and other regions using IALA System B, aids to navigation follow the Red Right Rising rule. When you’re inbound—heading upstream, upriver, or from sea to land—keep red markers to your starboard (right) side. The numbers on those markers will increase as you go. That rising number pattern is your key clue that you’re going the “inbound” direction. When outbound—heading toward the sea or downriver—reverse it. Green to starboard, red to port, and buoy numbers decrease.

You may have heard the old saying “Red Right Returning.” While catchy, it’s vague—returning from where? Red Right Rising is better. It connects to observable facts:

- Increasing buoy numbers

- Inland movement

- (Often) upstream travel

All things you can verify on your chart and on the water.

A commonly cited “exception” is the Intracoastal Waterway (ICW), which runs from Norfolk, VA to Brownsville, TX. Mariners like to joke that “Red, Right, Returning to Brownsville” applies here. It’s not really an exception—on the ICW, “inbound” means south and west, following the system’s increasing mile markers. Red Right Rising still works, as long as you recognize what “rising” means in this context.

Along the Intracoastal Waterway, keep an eye out for yellow symbols—squares and triangles—on buoys and daymarks. These don’t replace the regular red and green aids. They overlay them, marking the ICW’s inland route as it weaves through different local waterways.

When you’re generally south/west-bound (the ICW’s “inbound” direction toward Brownsville, TX),

- Yellow triangles go to starboard,

- Yellow squares go to port.

If you’re generally north/east-bound, just reverse it:

- Yellow squares to starboard,

- Yellow triangles to port.

This system helps you follow the ICW even when it veers away from the compass—sometimes taking you east, west, or upriver. When in doubt, trust the yellow symbols—they define the ICW route, even if local geography suggests otherwise.

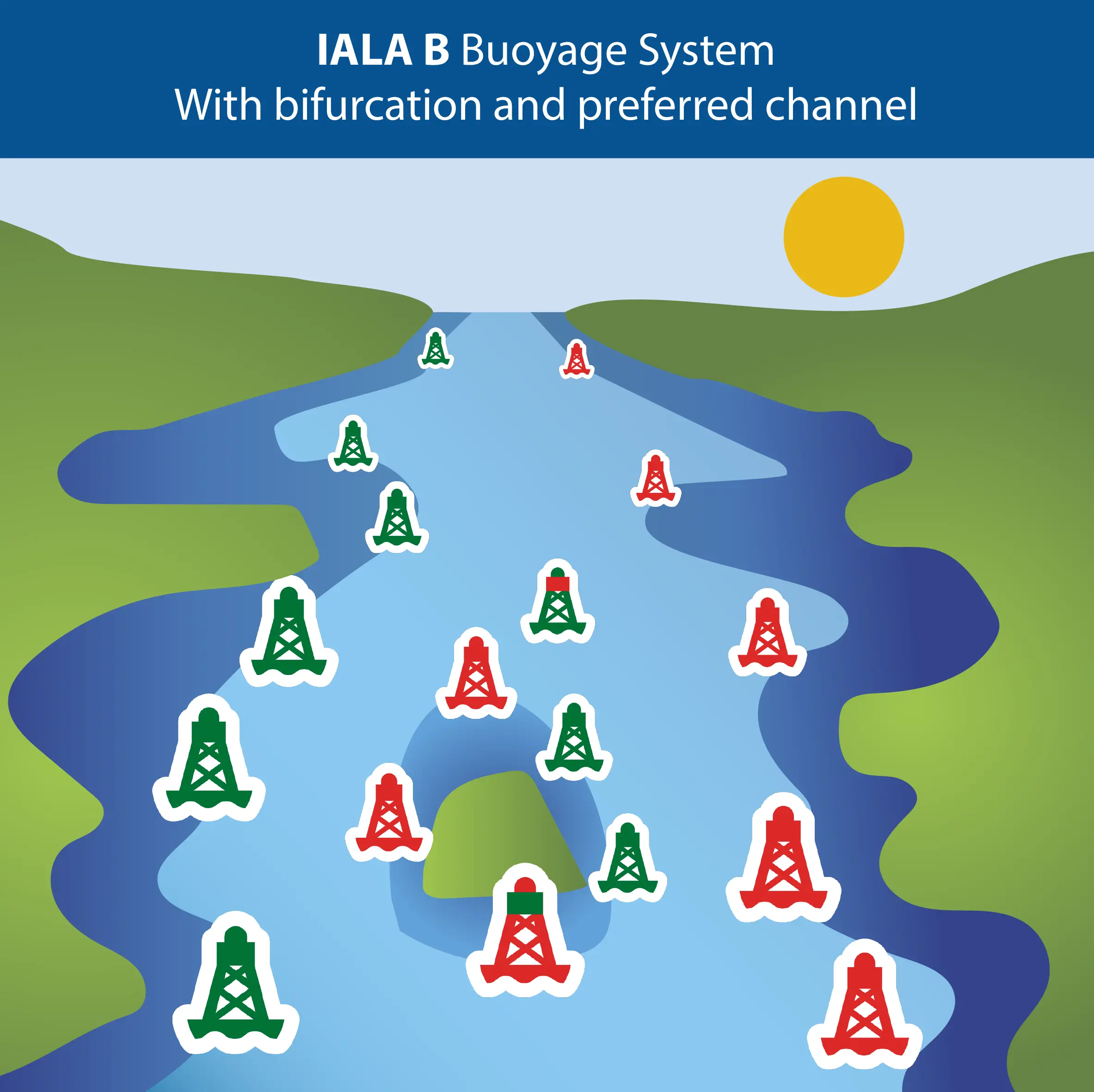

Bifurcation Buoys: Choosing the Right Split

When channels divide or intersect, keep an eye out for bifurcation buoys—they have horizontal red and green bands and signal a junction. You may have heard these referred to as “junction buoys” in some circles. These markers tell you which side is the preferred channel, depending on your direction of travel.

To interpret them:

- Red over green: The preferred channel is to port. If you’re heading inbound (upstream or upriver), treat it like a red buoy—pass it on your starboard side.

- Green over red: The preferred channel is to starboard. Inbound, treat it like a green buoy—pass it on your port side.

If you’re headed outbound (toward the sea or outbound/downriver), reverse the logic just like you would with other lateral buoys.

These junction markers are easy to overlook but important—especially where rivers split, ICW spurs branch off, or coastal inlets fork. Use your chart to verify your intended route, and double-check the buoy’s top band before committing to the turn.

Final Thoughts

Marked channels are tools—not commandments. Their purpose is to guide vessels safely, but it’s up to the mariner to apply judgment based on vessel draft, traffic, charted data, and local conditions.

Autorouting, chartplotters, and track overlays are helpful planning aids. But no matter how sophisticated your nav app is, nothing beats a pair of eyes on the water and a head in the game.

Stay aware, stay off the hard stuff, and enjoy the ride.

TL:DR Cheat Sheet

- Stay in: inlets, rivers, unfamiliar areas, shifting shoals, or poor visibility.

- Leave it: deep open waters, when avoiding traffic, or for anchoring.

- Use your eyes: Charts lie, markers drift, and depths change.

- Talk to the big boys: When unsure, hail commercial traffic on VHF 13/16.